Jul 18, 2018 - Equality between women and men, or gender equality, is a. The Western Balkan countries have taken steps to advance women's rights in recent years. That women face in the Western Balkans, such as their weaker roles in. 1 Country Comparison in Gender Roles Between Nigeria and U.S.A Introduction Nigeria is a nation situated in the West Africa. It shares borders with neighboring countries; in the North is Niger, Benin Republic on the West and in the East Cameroon and Chad.

Image sourceBy Teodora Rebrisorean, Institute for Cultural Diplomacy.The rise of fundamentalism in the Middle East has reinforced the idea that Islam is ubiquitous in culture and politics, that tradition is highly respected and women’s status is low. Legal issues and the status of women in the Middle East are quite different of those of women in the Western society. The social position of women in Muslim countries is worse than anywhere else, for example a woman can work and travel only with the written permission of her husband or male guardian, they can not obtain divorce without their husband’s cooperation who in contrast can obtain divorce simply by filling out a divorce form.

Many Islamic fundamentalist are against any change regarding women’s rights that can undermine male domination with regards to family and society. Their goals are to setup special curricula to train girls for their role as housewives, to restrict their access to political life, remove them from the legal profession, and to impose a rigid dress code. Despite these inequalities between men and women, for many of these women freedom of expression and equality do not seem meaningful goals to obtain. The majority of them see the Western culture as a danger for their native culture, brining with it the disintegration of families and social breakdown.If we look at Saudi Arabia, it is seen as the world’s most repressive country when it comes to women’s rights.

The Wahhabi form of Islam requires women to submit to male guardianship all their lives, which means that men decide where women go outside their home, which school to attend, whom she marries, whether she works and even what medical treatments she takes. Saudi Arabia remains the only country that forbids women to drive.Historically, Islam has resisted women’s rights and modernization. Unjust laws, discriminatory constitutions, and biased mentalities that do not recognize women as equal citizens violate women’s rights. A national, that is, a citizen, is defined as someone who is a native or naturalized member of a state. A national is entitled to the rights and privileges allotted to a free individual and to protection from the state.

However, in no country in the Middle East or Northern Africa are women granted full citizenship; in every country they are second-class citizens. In many cases, the laws and codes of the state work to reinforce gender inequality and exclusion from nationality. Unlike in the West, where the individual is the basic unit of the state, it is the family that is the basis of Arab states. This means that the state is primarily concerned with the protection of the family rather than the protection of the family’s individual members.

The rights of women are expressed solely in their roles as wives and mothers.Sources:. Modernizing Women: Gender and Social Change in the Middle East, SECOND EDITION- Valentine M.

MoghadamCenter for Cultural Diplomacy Studies PublicationInstitute for Cultural Diplomacy.

Women pray at Hussein mosque in the old city of Cairo. Reuters.Picture a woman in the Middle East, and probably the first thing that comes into your mind will be the hijab. You might not even envision a face, just the black shroud of the burqa or the niqab.Women's rights in the mostly Arab countries of the region are among theworst in the world, but it's more than that.

As Egyptian-Americanjournalist Mona Eltahawy writes in a for Foreign Policy,misogyny has become so endemic to Arab societies that it's not just awar on women, it's a destructive force tearing apart Arab economies andsocieties. How did misogyny become so deeply ingrained in theArab world? As Maya Mikdashi,'Gender is not the study of what is evident, it is an analysis of howwhat is evident came to be.' That's a much tougher task than catalogingthe awful and often socially accepted abuses of women in the Arab world.But they both matter, and Eltahawy's lengthy article on the formermight reveal more of the latter than she meant.There are twogeneral ways to think about the problem of misogyny in the Arab world.The first is to think of it as an Arab problem, an issue of what Arabsocieties and people are doing wrong. 'We have no freedoms because theyhate us,' Eltahawy writes, the first of many times she uses 'they' in asweeping indictment of the cultures spanning from Morocco to the ArabianPeninsula. 'Yes: They hate us.

It must be said.' But is itreally that simple? If that misogyny is so innately Arab, why is theresuch wide variance between Arab societies? Why did Egypt's hateful'they' elect only 2 percent women to its post-revolutionary legislature,while Tunisia's hateful 'they' elected 27 percent, far short of halfbut still significantly more than America's 17 percent? Why are somany misogynist Arab practicesin the non-Arab societies of sub-Saharan Africa or South Asia? Afterall, nearly every society in history has struggled with sexism, andmaybe still is. Just in the U.S., for example, women could not voteuntil 1920; even today, their access to basic reproductive health careis.We don't think about this as an issue of American men, white men, orChristian men innately and irreducibly hating women.

Why, then, shouldwe be so ready to believe it about Arab Muslims? A number ofArab Muslim feminists have criticized the article as reinforcingreductive, Western perceptions of Arabs as particularly and innatelybarbaric. Nahed Eltantawythe piece of representing Arab women 'as the Oriental Other, weak,helpless and submissive, oppressed by Islam and the Muslim male, thisugly, barbaric monster.' Samia Errazzouki at 'the monolithic representation of women in the region.' Roqayah Chamseddine,'Not only has Eltahawy demonized the men of the Middle East andconfined them into one role, that of eternal tormentors, as her Westernaudience claps and cheers, she has not provided a way forward for thesemen.' Dima Khatib,'Arab society is not as barbaric as you present it in the article.'

Hyper-v vs vmware. It does probably 90% of everything I need without any issues, and has no additional licensing cost. VMware has some advantages for third party stuff, like OVAs and some software is better at talking to a vCenter than talking to Hyper-V hosts, but it is 'good enough' for a lot of people.It is really nice that all the fun technology like clustering, replication, etc are built into the base technology and don't require expensive additional licensing to unlock.

Shelamented the article as enhancing 'a stereotype full of overwhelminggeneralizations that contributes to the widening cultural rift betweenour society and other societies, and the increase of racism towardsus.' Dozens, maybe hundreds, of reports and papers comparewomen's rights and treatment across countries, and they all rank Arabstates low on the list.

But maybe not as close to the bottom as you'dthink. A 2011 World Economic Forum report on national gender gaps put fourArab states in the bottom 10; the bottom 25 includes 10 Arab states,more than half of them.

But sub-Saharan African countries tend to rankeven more poorly. And so do South Asian societies - where a population ofnearly five times as many women as live in the Middle East endure some of the in the world today.

Also in 2011, Newsweek several reports and statistics on women's rights and quality of life. Theirincluded only one Arab country in the bottom 10 (Yemen) and one more inthe bottom 25 (Saudi Arabia, although we might also count Sudan).That's not to downplay the harm and severity of the problem in Arabsocieties, but a reminder that 'misogyny' and 'Arab' are not assynonymous as we sometimes treat them to be. Some of the most important architects of institutionalized Arab misogyny weren't actually Arab. They wereTurkish - or, as they called themselves at the time, Ottoman -British, and French.

These foreigners ruled Arabs for centuries,twisting the cultures to accommodate their dominance. One of theirfavorite tricks was to buy the submission of men by offering themabsolute power over women.

The foreign overlords ruled the publicsphere, local men ruled the private sphere, and women got nothing;academic Deniz Kandiyoti called this the'patriarchal bargain.' Colonial powers employed it in the Middle East,sub-Saharan Africa, and in South Asia, promoting misogynist ideas andmisogynist men who might have otherwise stayed on the margins, slowlybut surely ingraining these ideas into the societies.

Western Countries Vs Eastern Countries

Of course,those first seeds of misogyny had to come from somewhere. Theevolutionary explanations are controversial.

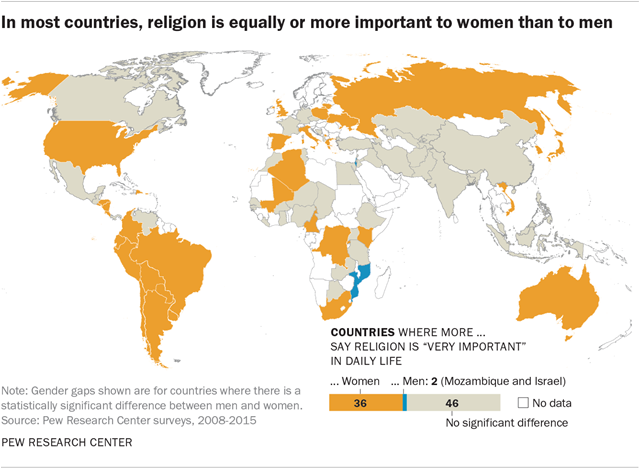

Some say that it's simplybecause men are bigger and could fight their way to dominance; some thatmen seek to control women, and particularly female sexuality, out of asubconscious fear being of cuckolded and raising another man's child;others that the rise of the nation-state promoted the role of warfare insociety, which meant the physically stronger gender took on more power.You don't hear these, or any of the other evolutionary theories, cited much. What you do hear cited is religion.LikeChristianity, Islam is an expansive and living religion.

It has movedwith the currents of history, and its billion-plus practitioners bring awide spectrum of interpretations and beliefs. The colonial rulers whoconquered Muslim societies were skilled at pulling out the slightestjustification for their 'patriarchal bargain.' They promoted thereligious leaders who were willing to take this bargain and suppressedthose who objected. This is a big part of how misogynistic practices becameespecially common in the Muslim world (another reason is that, when theWest later promoted secular rulers, anti-colonialists adopted extremereligious interpretations as a way to oppose them). 'They enshrinedtheir gentleman's agreement in the realm of the sacred by elevatingtheir religious family laws to state laws,' anthropologist Suad Josephwrote in her 2000, Gender and Citizenship in the Middle East.' Women and children were the inevitable chips with which the politicaland religious leaders bargained.' Some misogynist practices predatedcolonialism.

But many of those, for example female genital mutilation,also predated Islam. Arabs have endured centuries of brutal,authoritarian rule, and this could also play a role. A Western femalejournalist who spent years in the region, where she endured some of theregion's infamous street harassment, told me that she sensed herharassers may have been acting in part out of misery, anger, and their ownemasculation. Enduring the daily torments and humiliations of life underthe Egyptian or Syrian or Algerian secret police, she suggested, mightmake an Arab man more likely to reassert his lost manhood by taking itout on women.The intersection of race and gender is tough todiscuss candidly. If we want to understand why an Egyptian man beats hiswife, it's right and good to condemn him for doing it, but it's notenough.

We also have to discuss the bigger forces that are guiding him,even if that makes us uncomfortable because it feels like we're excusinghim. For decades, that conversation has gotten tripped up by issues ofrace and post-colonial relations that are always present but often toosensitive to address directly. Spend some time in the MiddleEast or North Africa talking about gender and you might hear theexpression, 'My Arab brother before my Western sister,' a warning to bequiet about injustice so as not to give the West any more excuses tocondescend and dictate. The fact that feminism is broadly (and wrongly)considered a Western idea has made it tougher for proponents. Aftercenturies of Western colonialism, bombings, invasions, and occupation,Arab men can dismiss the calls for gender equality as just another formof imposition, insisting that Arab culture does it differently.

Thelouder our calls for gender equality get, the easier they are to waveaway.Eltahawy's personal background, unfortunately, might play a role in how some of her critics are responding. She lives mostly in the West, writesmostly for Western publications, and speaks American-accented English,all of which complicates her position and risks making her ideas seem asWesternized as she is. That's neither fair nor a reflection of the merit of her ideas, but it mightinform the backlash, and it might tell us something about why the conversation she's trying to start has been stalled for so long. The Arab Muslimwomen who criticized Eltahawy have been outspoken proponents of Arabfeminism for years. So their backlash isn't about 'Arab brother beforeWestern sister,' but it does show the extreme sensitivity aboutanything that could portray Arab misogyny as somehow particular to Arabsociety or Islam.

It's not Eltahawy's job to tiptoe around Arab culturalanxieties about Western-imposed values, but the fact that her pieceseems to have raised those anxieties more than it has awakened Arab maleself-awareness is an important reminder that the exploitation of Arabwomen is about more than just gender. As some of Eltahawy's defendershave put it to me, the patriarchal societies of the Arab world need tobe jolted into awareness of the harm they're doing themselves. They'reright, but this article doesn't seem to have done it.We want to hear what you think about this article. To the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.